Suno's Army: Meet the Creators Redefining Music with AI

How AI Is Reshaping Content Creation & Consumption—Through the Lens of AI Music

中文版 | English Version

Maybe?!

Summer 2024, 2 AM, somewhere in the Canadian prairies where the only thing open at this hour is Jayden’s laptop. He sits with headphones on, fingers hovering over his RGB keyboard. This Canadian guy who’s never touched an instrument is about to complete a song that will appear on a Times Square billboard.

The catch: strictly speaking, he didn’t write a single note.

“I always felt like I couldn’t do it,” Jayden says. “I don’t play instruments, never studied music, never performed live—it was intimidating.” Fourteen months ago, he discovered Suno.ai—a platform where you type a few words and AI generates complete songs. Within hours, he was creating professional-quality music with his own lyrics. Months later, he beat thousands of competitors to win Suno’s inaugural “Summer of Suno” creation contest.

⬆️“Maybe?!“ on Times Square, New York

Up to 12 million people worldwide already use Suno AI to make music. Some post their creations on TikTok, building millions of followers. These AI-generated songs accumulate hundreds of millions of streams on Spotify, sometimes becoming chart-topping hits. This is beginning to shift the status quo of music creation, promotion, and consumption that has long been dominated by the “Big 3.”

For decades, three companies have dominated the global music landscape. Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, and Warner Music Group—the “Big Three”—collectively control approximately 70% of the $30 billion global recorded music market (IFPI, 2025). Every megastar you can name is signed to one of them. The system operates like an elegant feudal structure: they control not just the artists but the entire value chain—recording studios, production houses, media promotion, playlist placement, distribution networks, and the master recordings themselves.

Lisbon “Gothic Girl”

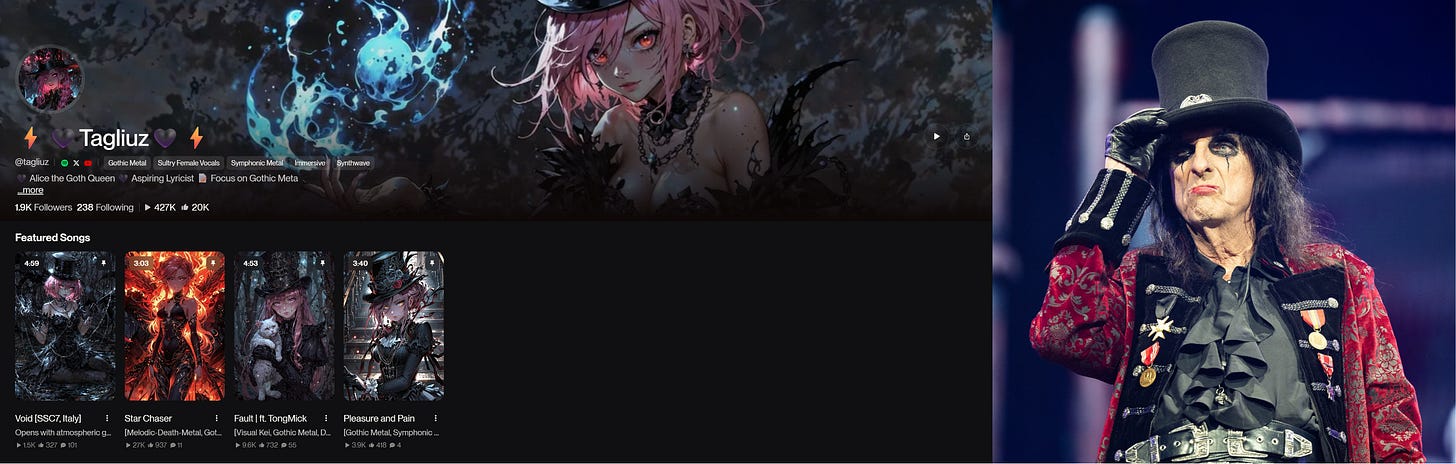

Thirty-year-old Italian programmer Tagliuz who lives in Lisbon Portugal created Alice—a pink-haired, orange-eyed gothic metal singer.

“I’m sick of those garbage,” Tagliuz tells me with his Italian accent, “empty songs are everywhere, repetitively boring.” So he decided to create music he wanted to hear himself, channeling it through a 2D character inspired by Alice Cooper.

Tagliuz first uses Leonardo AI to generate a consistent Gothic visual imagery for Alice, repeatedly fine-tuning prompts to maintain character trait consistency. For audio, he relies on Suno’s Persona feature, training samples to maintain her vocal recognition. “The whole process requires back and forth human intervention,” Tagliuz explains to me defensively. “It’s not just pushing buttons. You have to actively participate in AI’s creative process.” AI creators often need to defend their creative contributions against the misconception that AIGC is just pushing buttons.

Since the 1970s, Alice Cooper has shocked the rock world with provocative stage performances. His heavy makeup, distinctive styling, and theatrical shows not only redefined rock aesthetics but became symbols of creative freedom and self-expression. For many fans, Alice Cooper represents the courage to challenge social norms and refuse to be bound by predetermined identities—which is why his music and image continue to inspire those seeking authentic self-expression.

Then everything came to a sudden halt. Alice Cooper made controversial comments about transgender issues in an interview, shattering his image for many fans. Coincidentally, Tagliuz has stopped updating all content—Alice’s Suno, Spotify, and YouTube pages have remained inactive since July 2025.

Brazilian Hit Factory

On the other side of the Atlantic in São Paulo, Brazil, 23-year-old Raul achieved what many musicians dream of: 2 songs on Spotify Viral 50 chart at the same time. He created his own Blow Records label, specializing in using AI to convert contemporary Brazilian hits into retro blues and disco versions.

“I never release without communicating with original artists first,” Raul says. His strategy is to first create AI-generated clips under one minute, and if they go viral, use that success as leverage to request formal authorization from original creators before official release.

Raul’s success—millions of TikTok videos using his songs, people creating choreography to his tracks, hundreds of thousands of Spotify listeners—proves AI music’s commercial viability to every stakeholder in this game.

When AI Work Gets Stolen

YouTube creator Hashem Al-Ghaili, with millions of followers worldwide, created the soundtrack “Mushroom Cloud“ for his short film “Hiroshima“ made with a suite of AIGC tools. But before he could officially release it, third parties pirated it and uploaded it to major streaming platforms under their names. Hashem received copyright claims on Facebook—which he disputed, though they keep recurring. When he asked the platforms to remove unauthorized uploads, they called it a “gray area” and declined to act.

To protect original works and meet “sufficient human creative input” requirements, AI creators must take extreme measures. For another satirical short film about a clone musician called “Kira,” Hashem saved 600 pages of ChatGPT conversation records documenting the entire creative process—from story conception to character design, technical implementation to post-production optimization. He told me that Hollywood production companies have already approached him to purchase his original short film rights for full movie development.

TikTok’s Rapping STEM Teachers

Unlike overseas hit songs, Douyin (a.k.a Chinese TikTok) creators took a different path with “knowledge made catchy” short videos:

“It struggles forward with its load/The cargo’s size makes progress slow/Hundreds of times its own head/But the little protein never shows dread”—biology knowledge about proteins transformed into rhyming lyrics, set to an addictive melody reminiscent of the BGM in “Shawarma Legend.” Douyin has numerous similar accounts: “Hu Xiaoxian“ covers science and engineering history, “Rap & Science“ popularizes math concepts, “English Enlightenment UXA“ teaches Zoology with English lyrics, and the “Shun Hua Sings Herbs“ series focuses on plants.

Douyin platform’s algorithm seems to encourage educational content, making these videos highly viewed. More importantly, they make knowledge enter your brain in a relaxed way. Comments say: “Did I just learn something? /s [Confused emoji]” Beyond humor, users rarely discuss whether videos and music are generated by AI, rather they focus more on the content itself, showing knowledge-infused rap actually effective for educational purposes.

The relative simple workflow-based production of these viral content format mean more people joining in. However for monetization, besides platform revenue sharing, general knowledge fields have low conversion rate—users won’t pay for this. AI education rappers on Douyin told me that they haven’t found a reliable path to scale up the revenue stream.

The Voiceless Singer’s Voice

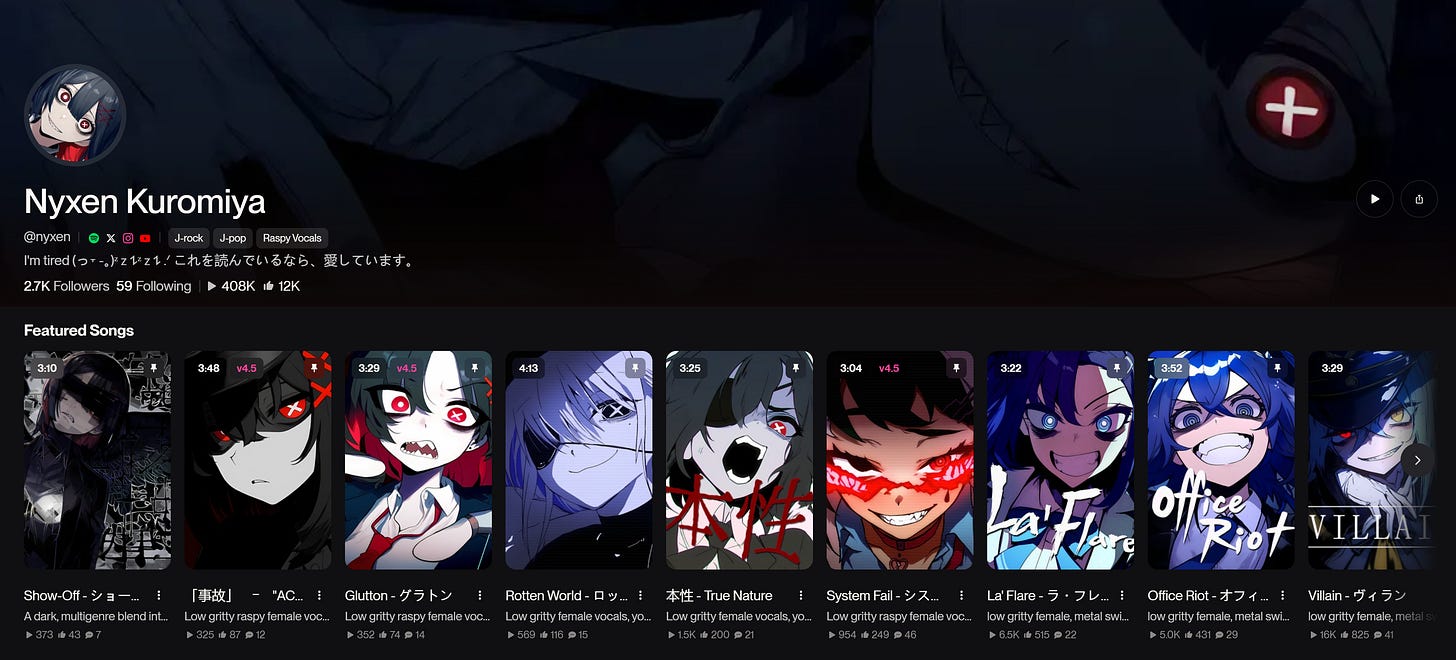

Perhaps no story better embodies AI creation tools’ democratizing potential beyond commercial value than Japanese user Nyxen. Due to speech impairment, she can only communicate with me through text.

“AI gave me a voice [pray emoji],” she types in Discord, occasionally throwing in an anime emoji. For her, AI isn’t just a music-making tool—through Suno, she gives an anime-style virtual character a unique voice, accumulating thousands of monthly Spotify listeners. Nyxen’s creative process reflects many AI musicians’ experimental qualities. “I originally just wrote lyrics for fun, trying to make them sound perfect on Suno. Never thought deeply about becoming a professional musician,” she types to me. This casual attitude—creating for joy rather than livelihood—is common in the Suno community.

Swiss “Godfather”

Even more remarkably, Swiss creator TongMick became a spiritual leader in the Suno community. He uses thousands of tweets to promote other Suno platform music creators. Since last August, his “My Favorite Suno Artists” series has featured 241 creators and continues updating.

“My own music has no fixed style because I always get new inspiration in the co-creation process with AI.” He deliberately maintains anonymity, choosing a cute white cat as his avatar. For him, what matters isn’t money but speaking for this community of tens of millions of users.

However, TongMick has growing concerns about platform changes. His frustrations with Suno’s direction culminated in leading a community open letter to the Suno team in September 2025, signed by dozens of creators who raised issues about trending chart manipulation, broken iOS features, and lack of transparency in discovery algorithms. “The global trending charts are increasingly dominated by accounts using artificial engagement,” the letter states, “pushing genuine creators out of visibility.”

TongMick’s day job is in the audio-visual equipment space. Having witnessed the evolution from cassette player to iPod and streaming services, he thinks AI music is just starting and predicts that “within two to three years, there will definitely be charts specifically for AI.” His vision isn’t AI replacing human creation but coexistence—two parallel ecosystems serving different audiences.

Suno Goes to Court

While creators immerse themselves in AI music’s creative pleasure, Suno’s management team faces court battles against the Big 3. Last June, Universal, Sony, and Warner jointly sued Suno, alleging unauthorized use of copyrighted music to train AI models. Almost simultaneously, independent musicians also filed class action lawsuits claiming Suno-generated music directly infringes their work copyrights.

In its August 2025 motion to dismiss, Suno‘s lawyer Andrew M. Gass argued that copyright law only protects against copying “actual sounds.” Since Suno “exclusively generates new sounds, rather than stitching together samples,” the company claims “no Suno output can infringe the rights in anything in the training set, as a matter of law.” It’s a technical argument that sidesteps the question of whether training on copyrighted music is legal, focusing instead on whether the output itself contains copied audio.

The case is still pending, but the stakes extend far beyond Suno. California federal judges have recently sided with AI companies in several intellectual property disputes, suggesting that training on copyrighted material could constitute “fair use,” basically giving other AI companies a green light to go ahead. Still, Suno faces international lawsuits from music copyright organizations—even an American victory won’t end the global legal battle.

While the lawsuit plays out in the public eye, Suno is also quietly positioning itself as more than just a music generation tool—it’s building an army of creator-advocates. These everyday users, who have experienced firsthand how AI democratizes music creation, provide powerful testimonials against claims that Suno merely “stitches” existing works. This grassroots community—teachers creating educational raps, voice-impaired individuals finding expression, and hobbyists creating viral hits—reinforces the narrative that Suno enables genuine creativity rather than facilitating copyright infringement.

Rewriting Game Rules with UGC

As legal proceedings continue, this global community’s diverse creations may serve as compelling evidence that AIGC music empowers original expression rather than plagiarism—potentially Suno’s strongest defense in a landscape still adapting to AI’s creative potential.

Before AIGC, TikTok already proved that 15 second clips could make or break a song—bedroom producers went from nobody to millions of streams because their music caught a viral moment on TikTok—disrupting Big 3’s dominance on music promotion.

In September 2025, Suno quietly began testing “Hooks,” and on October 1st, both Hooks and OpenAI’s Sora 2 launched publicly on the same day. The coincidental timing reveals a shared philosophy that’s reshaping how AI companies approach product development: from applying models to existing products to building models specifically for user products in mind.

What’s truly remarkable about both of these products—beyond their TikTok-like interfaces—are the “Remix” features that allow content to be audio-visual, social and endlessly reinterpretable.

Suno Hooks lets users pair their AI-generated songs with 10-20 second video clips and publish them to a TikTok-style feed where other Suno users can remix from the sound. Sora 2 takes it one-step further—users can “remix” any published video by prompting, inserting their own faces via “cameos,” or swapping visual styles while keeping the original structure. Both platforms share the same premise: content isn’t meant to be finished. It’s meant to inspire the next User-Generated Content to be watched by more users on the platform.

This shift has profound implications. When TikTok lowered the bar for video creation, it didn’t make everyone a filmmaker—it changed what counted as video worth watching. Now AI is pushing further: creation and consumption are merging into a single social loop. You don’t just watch a Hook; you remix it. The line between audience and creator dissolves because the content isn’t complete without engagement.

As for Jayden and the other Suno creators, after his moment of fame, Jayden returned to his normal life in Lloydminster. He still writes songs when inspiration strikes. The “Summer of Suno” competition he won was just the beginning—the contest has since reached its ninth iteration, still drawing thousands of new creators who dream of their own Times Square moment.